Postcards

Sydney Jewish Museum 2002

Postcards: Landscapes and memories

Memory has a curious quality. It exists always in the present, yet refers to a time before. It’s both resilient and fragile, it can be manipulated by desire and suppressed through fear. It can be moulded to fit what confronts us now in order to defend or explain what has been. Nowhere is the political fragility of memory more acute than in the Holocaust and its traces on our lives and consciousness, on the culture and its capacity for resilient adaptation.

Naomi Ullmann, herself the daughter of Holocaust survivors and therefore marked in particular ways by the memories of others, has chosen to explore the psychic and physical terrains of the Holocaust through a series of 35 painted postcards and postcard like projections. Each image is placed on a board (or etched/blasted into a transparent glass panel), and hung in a space. The space is random, the accidental placing of objects and people so they collide with or avoid catastrophe; nothing predictable, nothing foreseeable, nothing avoidable.

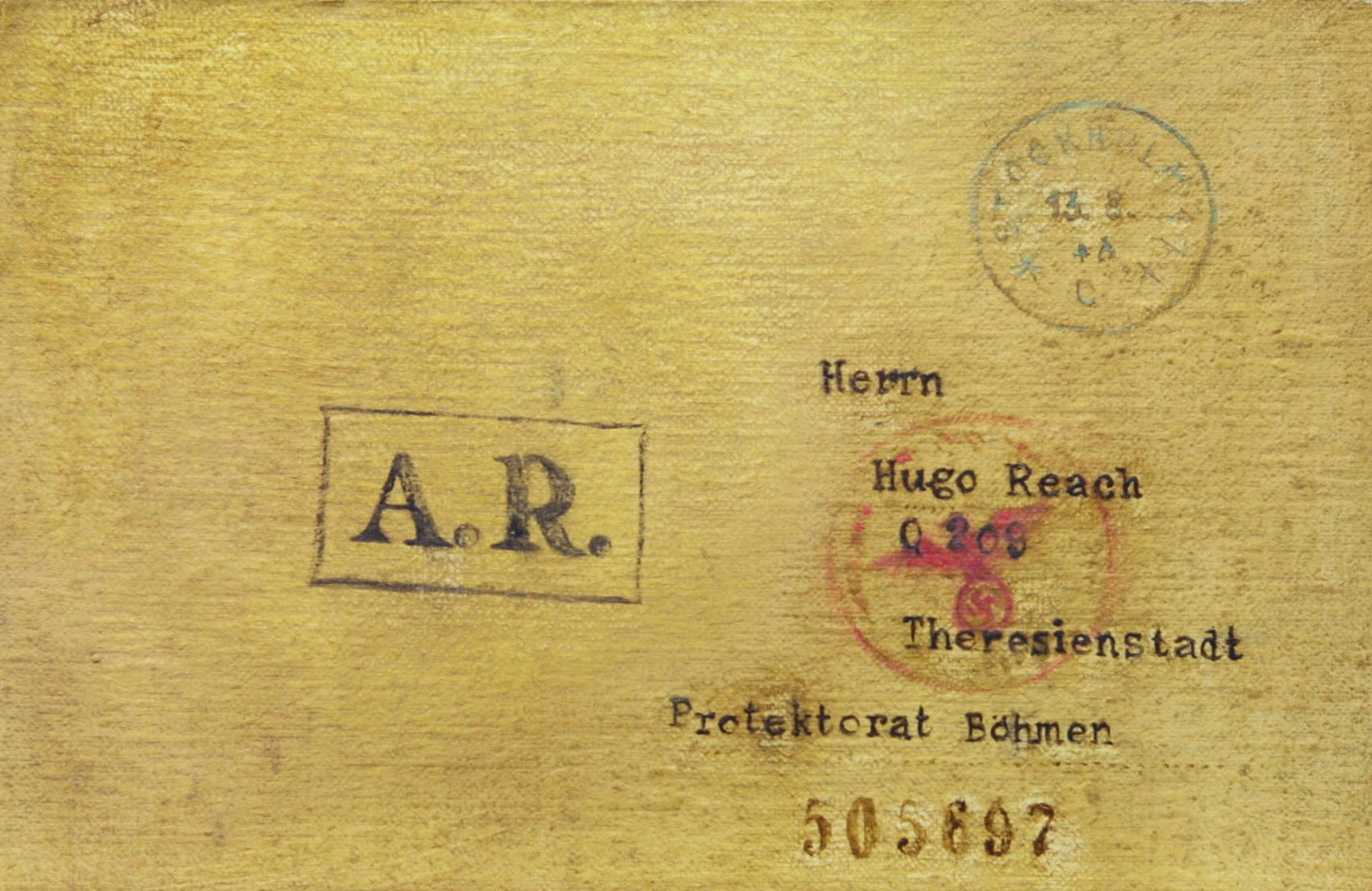

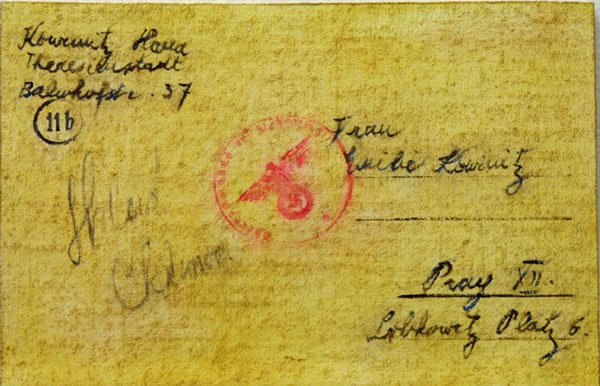

The overarching binding link is that of a Nazi Eagle perched on a Kakenkreuz, the swastika, once (and still) the mystical Hindu wheel of life, appropriated by the Nazis as the symbol of death. The particular image is a postmark stamp, in blood red, taken from the address side of a postcard from my grandfather in the Lodz Ghetto to my father by that time safe in Kobe, Japan, in 1941. It was their last communication.

We can begin anywhere, but let us do so with a series of pre-war images, Jewish people enjoying themselves and revelling in the complex and cultural mix of central and eastern Europe, sending each other greetings and celebrating festivals and holy-days. A joy flight, colourful ethnic clothes, the energy of life, one that was exhilaratingly flamboyant, yet soon to be stopped. Then images of places, Ullmann’s family town of Campulung, mine of Lodz, the edge of the red eagle and its sinister perch breaking the aesthetic, corroding the touristic fascination of the viewer.

Forests and birds, shadows on landscapes, the intensity of light and shade with glimpses of what lies outside the forest, the forest as refuge and trap, as haven and target. Here we sense the flight, the slipping between the pools of darkness, the threat of exposure to the sight of the hunting enemy. A false step, a voice crying out in the silence, and all can be lost.

Then stark moments of suppressed pain – postcards from Lodz, from Theresienstadt, the apparently mundane cloaking the intensity and immensity of suffering and despair. Nothing can be really said, though everything is, in the bland bureaucratic efficiency of the processing by the post offices of the Reich. Lives left behind by those who survive, through luck or flight or both.

Bits of survival emerge, free of the Eagle – a tin of Satsuma plums from the local supermarket, redolent of the “War Chest”, the store of goods held by Naomi’s parents, “just in case”. This is now, not then. A tin of ersatz frosted honey, a product made by German Jewish refugees in Shanghai in 1943, in the area of Hongkew, the designated area into which the Japanese herded the refugees. An embroidered photo-album, the sinuous Chinese dragon entwining the Shanghai”, the original containing the exile photos of a young Hungarian Jewish family that lived there, on the edge of free and not-free.

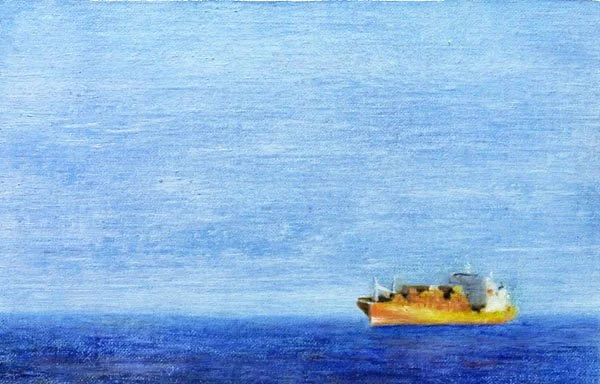

And then, two very contemporary images, “children overboard” and a cargo boat that can only be the “Tampa”. These images link past to present, throw into sharp relief the politics of memory, who remembers what things for what purposes in what situations with what outcomes: yet the boat is also a present shadow of a past infamy, the ship of fools that came so close to rescuing Jewish refugees from Germany, but was then turned back from Cuba and the USA, and offloaded its human cargo into lives that ended in their extermination as the Holocaust rolled west across Europe.

Ullmann has created an intensely powerful landscape through which we move as narrators of its meanings. She expects us to reflect and think, to make connections, to use the images to tell ourselves stories that are ultimately of our own making. She triggers responses, activating shards of insight, opening up connections like lightning strikes between unlikely points of symbiosis. The breathing quickens, we turn between the points, layers are placed askew, and as we begin to claw our way through the responses they trigger in our own minds, we discover the power of memory for each next step we might take.

Professor Andrew Jakubowisz

Professor of Sociology

University of Technology, Sydney

2002

Bosnian Jewish women in Spanish costume, 2001 oil on linen on board 15x10cm

The Happy Couple, oil on linen on board 2001 15x10cm

Postcard 2001 oil on linen on board 15x10cm

Overboard, 2002 oil on linen on board 15x10cm

Postcard (ii), 2002 oil on linen on board 15x10cm

Shame 2002 oil on linen on board 15x10cm

Postcard (iii), 2001 oil on linen on board 15x10cm

Letter to my sweetheart, oil on linen on board 2001 15x10cm

Foochow Road Shanghai, 2001 oil on linen on board 15x10cm

Thererienstadt, 2001 oil on linen on board 15x10cm

Cumpulung, 2001 oil on linen on board 15x10cm

Jewish dancers Tunisia, 2001 oil on linen on board 15x10cm